The unprecedented confrontation between President Donald Trump and the Federal Reserve (Fed) is reaching a climax in the U.S. Supreme Court, revolving around the power to fire a Fed governor – something that has never happened in the central bank’s 111-year history.

The upcoming ruling will not only decide the fate of Fed Governor Lisa Cook, but could also shake the principle of monetary independence in the United States, challenge the lines of power between the White House and the central bank, and create a seismic shift in global financial markets.

The U.S. Supreme Court building in Washington, D.C. Photo: Chip Somodevilla/Getty Images

The U.S. Supreme Court building in Washington, D.C. Photo: Chip Somodevilla/Getty Images

According to CNN, after repeatedly allowing Trump to remove leaders of other independent agencies, the Supreme Court, with its conservative majority, appeared to draw a line on the central bank last spring.

In a statement, the Court wrote that the Fed – with its enormous influence over the economy – is protected from political manipulation because of its “unique structure” and “distinctive historical traditions.”

The scope of this rare exception will be tested next Wednesday, when the court hears oral arguments in a case involving Lisa Cook, a Fed governor whom Trump sought to fire last summer, following allegations that she committed mortgage fraud by reporting two different homes as her primary residences. (Cook has denied any wrongdoing.)

This is considered one of the most important cases the Supreme Court has heard in recent years concerning presidential power and the economy.

“What the court is facing is the question: how significant a hurdle does this exception actually create to the president’s control over the Fed? This case isn’t just about Lisa Cook. We’re going to find out what the real relationship between the central bank and the president is,” said Lev Menand, a law professor at Columbia University and author of a 2022 book on central banking.

If Trump ultimately succeeds in firing Cook, it would be the first time in the Fed’s 111-year history that a president has removed a central bank governor from office.

Meanwhile, the Trump administration escalated tensions this month by launching a criminal investigation into Federal Reserve Chairman Jerome Powell. While this case is outside the jurisdiction of the Supreme Court, it is likely still on the minds of the justices.

Cook warned that if the court sided with Trump, it would “wipe out the independence” of the Fed and cause “chaos and disruption” to US financial markets.

That’s why she and her lawyers placed a great deal of faith in what the court wrote about the Fed in last year’s ruling.

“It is unlikely that Mr. Trump will be able to ‘persuade the court to accept his argument,’” Cook wrote in a submission to the judges last year, “especially after the court itself has proactively emphasized the unique position and distinct history of the Federal Reserve.”

The battle is not over yet.

President Donald Trump and Federal Reserve Chair Lisa Cook. Photo: Chip Somodeville/Al Drago/Getty Images

President Donald Trump and Federal Reserve Chair Lisa Cook. Photo: Chip Somodeville/Al Drago/Getty Images

From the administration’s perspective, the arguments focused on more technical points, claiming that Cook was not entitled to review additional allegations beyond those she had already received before Trump sought to fire her.

“The Federal Reserve Board of Governors’ unique role in the American economy further increases the interest of the government and the public in ensuring that a morally compromised member does not continue to wield such immense power,” the U.S. Department of Justice argued before the Supreme Court last fall.

Trump fired Cook last August after an administration official accused her of mortgage fraud – a practice that could help borrowers obtain favorable loan terms. Subsequent documents revealed that Cook sometimes misrepresented her second home as a “vacation home.” Cook called these accusations “fabricated.”

Federal law allows the President to remove Fed members “for just cause,” so a core question for the Supreme Court is whether those allegations meet the “just cause” standard. Because the dismissal of leaders of independent agencies is rare, the answer is not clear.

After returning to the White House a year ago, Trump quickly acted to consolidate power within the executive branch. During that time, the Supreme Court allowed the president to temporarily remove board members from the Federal Trade Commission (FTC), the Consumer Product Safety Commission, the National Labor Relations Board, and the Council for the Defense of the Civil Service.

However, those lawsuits involved slightly different legal issues than the Fed case. In those other cases, Trump sought to fire board members without giving reason, despite federal law requiring proof of misconduct or negligence of duty.

For Ms. Cook, the Department of Justice believes the mortgage fraud allegations constitute sufficient grounds for prosecution.

A federal court in September temporarily blocked Cook’s firing, ruling that Trump had failed to demonstrate any conduct related to her work that harmed the public interest. A federal appeals court in Washington, D.C., refused to suspend that ruling, forcing Trump to quickly file an emergency appeal to the Supreme Court.

Instead of resolving the case through expedited procedures, the Supreme Court decided to hear the arguments orally.

And in a move that displeased the Trump administration, the court allowed Cook to remain in office while the case was reviewed.

Is the Fed a “special case” that the President cannot touch?

For months, lawyers representing leaders of independent agencies fired by President Donald Trump have repeatedly issued a simple but worrying warning: If the president has the power to dismiss the leaders of certain independent agencies, then in principle, he could do the same with the governors of the Federal Reserve (Fed).

This argument is considered quite reasonable, especially given that the Supreme Court is always cautious about rulings that could shock the markets and affect the US economy.

However, in an unsigned ruling published in May, the Supreme Court rejected that line of reasoning, stating that the Fed cannot be placed on par with other independent agencies.

According to the Court, the Fed is a “semi-private” institution with a unique structure and history, stemming from the first central banks of the United States more than two centuries ago. This difference, the Court argued, necessitates special treatment for the Fed.

This interpretation immediately drew a reaction from the minority in the Court. Judge Elena Kagan, along with two other liberal judges, argued that the majority’s reasoning was incomprehensible and lacked a clear foundation.

In her dissenting opinion, Ms. Kagan acknowledged she was “pleased” that the Court wanted to avoid putting the Fed at risk. However, she also pointed out that the majority’s defense of the Fed seemed “suddenly apparent” and not based on a sound system of reasoning.

“Today’s ruling is like an unsolved riddle,” she wrote.

According to Ms. Kagan, constitutionally speaking, the Fed’s independence is no different from that of other independent agencies – agencies that the Court allowed President Trump to interfere with and fire their leaders.

This view is also shared by many legal scholars. Professor Lev Menand, an expert on central banking, argues that the Supreme Court’s view of the Fed as an exception is unconvincing.

“This argument is both illogical and academically impractical. Many expect the Court to provide a clearer explanation of why the Fed is different, but I’m not very optimistic,” he remarked.

Conversely, some experts argue that the Fed’s history is sufficient justification for this particular approach. According to them, ever since the US Congress established the First and Second Federal Reserve Banks, day-to-day monetary control has been separated from the president to avoid political interference.

According to experts who support Governor Lisa Cook, the Fed’s original structure was designed to “decentralize power,” ensuring that decisions on interest rates and monetary policy were not influenced by short-term political interests.

For years, Trump has consistently criticized the Fed, arguing that it keeps interest rates too high, detrimental to economic growth. Critics argue that the administration’s targeting of Cook – and more recently Fed Chairman Jerome Powell – is essentially an attempt to pressure the Fed to lower interest rates.

In fact, the Fed has cut its benchmark interest rate three times in September, October, and December, citing economic indicators, not pressure from the White House.

Lisa Cook was one of the members who voted in favor of these interest rate cuts.

News

Germany declares Trump has crossed the ‘limit’, calls on the EU to ‘unite’ to make the US president ‘pay the price’.

Germany declares Trump has crossed a red line in the Greenland case. Germany considers the US President’s demand to annex Greenland…

A source close to the couple has just updated the current status of Tiger Woods and Vanessa Trump’s relationship: “Birds of a feather flock together.”

Insider claims Tiger Woods and Vanessa Trump are ‘each other’s ideal type’ after couple’s loved-up display at his lavish 50th…

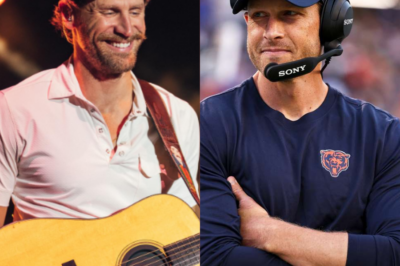

It turns out Chase Rice has a special connection with Chicago Bears head coach Ben Johnson: Johnson stole Rice’s girlfriend back in high school!

Chicago Bears Head Coach Ben Johnson Once Stole Country Star Chase Rice’s Date – Kind Of: “I’m Still Mad” Tribune…

Tennessee Governor Declares Jan. 19 ‘Dolly Parton Day’

The honor arrives just in time for Parton’s 80th birthday. Dolly Parton performs during “Dolly: An Original Musical” fireside chat…

Morgan Wallen denies using artificial intelligence (AI) for his new song: “Who would intentionally throw away their own meal?”

Morgan Wallen Denies A.I. Used for New Song ‘Country Music, Also Known as Country and Western or Simply Country, Is…

Quite stressful!!! Country music singer rips ‘bootlickin’ country artists’ supporting Donald Trump

Country singer Bryan Andrews has been making his way into the headlines for his music as well as his thoughts…

End of content

No more pages to load