On June 2, 2011, Amy Winehouse walked out of London’s Priory Clinic after what her representatives called an “assessment” for her drinking problem. The 27-year-old singer had checked in just days earlier at her father Mitch’s insistence, hoping to get sober before embarking on a 12-date European comeback tour. Her team announced she would continue treatment as an outpatient while performing. The plan seemed reasonable on paper. In reality, it was a catastrophe waiting to unfold.

Sixteen days later, on June 18, Amy Winehouse gave what would become her final full concert performance at Kalemegdan Park in Belgrade, Serbia, as part of the Tuborg Festival. What happened that night would shock the world and foreshadow a tragedy that was now just weeks away.

The warning signs appeared before Winehouse even reached the stage. She arrived at the venue an hour late, leaving thousands of Serbian fans waiting in the summer heat. When she finally emerged, it was immediately clear something was terribly wrong. The woman who had won five Grammy Awards just three years earlier—who had been hailed as one of her generation’s most talented vocalists—stumbled onto stage visibly intoxicated, barely able to stand.

“Hello Athens!” she slurred to the Belgrade crowd. Then, moments later: “Hello New York!” She had no idea where she was.

What followed was not a concert. It was a public breakdown, broadcast in real-time to an audience of thousands and, through mobile phone footage, eventually to millions around the world. Winehouse wandered aimlessly across the stage, swaying and losing her balance. She sat down mid-song. She threw down her microphone. She tossed a slipper into the crowd. She struggled to remember lyrics to songs she had performed hundreds of times—”Just Friends,” “Valerie,” “Addicted”—songs that had made her famous, now reduced to mumbled fragments.

Her backing singer, Zalon Thompson, did his best to salvage the disaster, whispering lyrics into her ear and singing louder to fill the gaps when Winehouse simply stopped. The band played on heroically, trying to create some semblance of a show from the wreckage unfolding before them.

The most heartbreaking moment came during “Some Unholy War.” Winehouse forgot the words. Thompson leaned in close and whispered them to her. In that instant, the full weight of what was happening seemed to crash down on her. She became emotional, her face crumpling as tears threatened. She knew she was failing. She knew the world was watching. The audience, their patience exhausted, began to boo.

The jeers grew louder. Some fans walked out. Others stayed, documenting the spectacle on their phones. Serbia’s defense minister, Dragan Šutanovac, who attended the festival, later called it “a huge shame and a disappointment.” Moby, who was also performing that day, recalled hearing “the audience booing louder than the music” from backstage. He saw Winehouse afterward, lying on a flight case, surrounded by people trying to help.

After less than an hour of this painful theater, the concert mercifully ended. Winehouse left the stage. Her team sent the band home on her private plane while her security guard, Reg Traviss, stayed with her in Istanbul for a few days. When she finally returned to London, she told her GP she couldn’t remember anything about the concert. She would later discover what happened by watching amateur footage posted on YouTube—forced to witness her own public humiliation through the phones of strangers.

On June 21, 2011—three days after Belgrade—her management announced the cancellation of the entire European tour. The statement read: “Everyone involved wishes to do everything they can to help her return to her best, and she will be given as long as it takes for this to happen.”

But time was something Amy Winehouse no longer had.

According to her father Mitch’s later accounts, Amy told him after Belgrade that she “really, really” wanted to stop drinking. For the rest of June and into early July, Mitch believed she was sober. When he saw her on July 10 and July 14, she seemed in good spirits. On July 20—just three days before her death—Amy made her final public appearance at the Roundhouse in Camden for the iTunes Festival. Her goddaughter, Dionne Bromfield, the first artist signed to Winehouse’s Lioness Records label, was performing with boy band The Wanted. Amy joined her onstage for the final song, a cover of The Shirelles’ “Mama Said.” She danced and sang very little, but witnesses said she seemed happy. She was seen patting her father’s manager on the stomach, saying, “Look after my dad.”

On July 21, Mitch visited Amy at her Camden home. He was flying to New York the next day, but she insisted he come over to look at family photographs she’d found. It was the last time he saw his daughter alive.

On the night of July 22, Amy Winehouse and her bodyguard Andrew Morris stayed up until 2 a.m. watching YouTube videos of her early performances—back when she was unknown, undamaged, full of promise. Morris remembered that Amy was laughing, in good spirits. At 10 a.m. the next morning, he checked on her. She appeared to be sleeping, so he let her rest.

At 3 p.m. on July 23, 2011, Morris realized something was wrong. The apartment was still quiet. Too quiet. Amy was in the same position as that morning. He checked for a pulse. There was none.

Amy Winehouse was found dead in her bed, empty vodka bottles scattered on the floor beside her. She was 27 years old. The coroner’s report would later reveal she had a blood alcohol level of .416%—more than five times the legal driving limit in the United Kingdom. The official cause of death: accidental alcohol poisoning.

Her brother Alex later told The Guardian that Amy’s long-term battle with bulimia had left her body weakened and more susceptible to the effects of alcohol. “She would have died eventually, the way she was going,” he said, “but what really killed her was the bulimia. I think that it left her weaker and more susceptible. Had she not had an eating disorder, she would have been physically stronger.”

Amy Winehouse’s death shocked the world, though those who knew her best admitted they weren’t surprised. Her public struggles with addiction had played out in tabloid headlines for years—stumbling out of Camden pubs, arguments with ex-husband Blake Fielder-Civil caught on camera, the irony of “Rehab” becoming her signature song while she clearly needed exactly that.

But Belgrade had been different. It wasn’t paparazzi photos or tabloid speculation. It was undeniable evidence, captured and shared globally, of a young woman in crisis. Some called it exploitation—the uploading and sharing of her breakdown. Others saw it as a cautionary tale. Many saw both.

The tragedy of Amy Winehouse is that her immense talent was never in question. Her second album, Back to Black, released in 2006, remains a masterpiece—five Grammy Awards, millions of copies sold worldwide, and a sound that influenced an entire generation of neo-soul artists from Adele to Sam Smith. Songs she wrote herself—”Rehab,” “You Know I’m No Good,” “Back to Black,” “Tears Dry on Their Own”—became anthems that will outlive everyone who heard them.

But between that album’s release and her death five years later, Amy Winehouse released no new music. Those years were consumed by addiction, toxic relationships, media scrutiny, and a spiraling descent that no amount of clinic visits or canceled tours could reverse.

Tony Bennett, who recorded “Body and Soul” with Winehouse in March 2011—her final recording—later said, “She was born with that jazz spirit. Some people think anyone could sing jazz, but they can’t. It’s a gift you’re either born with or you’re not. And Amy was born with that spirit.”

That spirit died on a Saturday afternoon in Camden, alone in a dirty apartment, surrounded by vodka bottles. Amy Winehouse became another member of the tragic “27 Club”—joining Jimi Hendrix, Janis Joplin, Jim Morrison, and Kurt Cobain as icons who burned too bright and died too young.

The Belgrade concert remains difficult to watch. But it’s also important—a stark reminder of what addiction looks like when the cameras are rolling, when there’s nowhere to hide, when a young woman who should have been receiving intensive care was instead pushed onto a stage in front of thousands.

Five weeks separated that disaster from her death. Five weeks that could have been spent in treatment, in healing, in genuine recovery. Instead, they were the final chapter of a story that should have had decades left to tell.

Amy Winehouse’s voice—that raw, soulful, utterly unique instrument—was silenced at 27. But the questions her death raised about how we treat struggling artists, how the media feeds on celebrity suffering, and how addiction destroys without mercy, continue to echo.

News

Bad Bunny Sparks Super Bowl Firestorm With Rumored Dress

Rumors of Bad Bunny wearing a dress at the Super Bowl halftime show ignite political backlash, raising questions about representation,…

Rod Stewart Slams ‘Draft Dodger’ Trump for Insulting NATO Troops

Rod Stewart called on President Donald Trump to apologize for his disparaging remarks about NATO troops, exhorting British Prime Minister Keir Starmer and Leader…

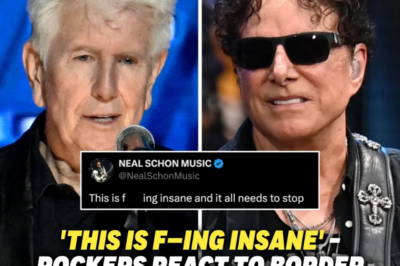

Rockers React to ‘Insane’ Border Patrol Killing of Alex Pretti

Graham Nash, Neal Schon, Tom Morello and other rock stars took to social media to react to a Border Patrol agent fatally shooting…

Bret Michaels Reacts After Poison Drummer Claims 40th Anniversary Tour Wasn’t Happening Due to Frontman’s Financial Demands

Michaels broke his silence in a Facebook post on Jan. 21 after Rikki Rockett alleged that the bandleader wanted $6…

BRET MICHAELS Breaks Silence On POISON Tour Rift After RIKKI ROCKETT’s Pay Dispute Claims

BRET MICHAELS Breaks Silence On POISON Tour Rift After RIKKI ROCKETT’s Pay Dispute Claims As rumors swirl over a stalled…

Listen to Def Leppard’s hard rocking new song ‘Rejoice’

“We love it. It’s hard rock for us. It’s got a bit more of an ‘oomph’ than stuff we’ve been…

End of content

No more pages to load