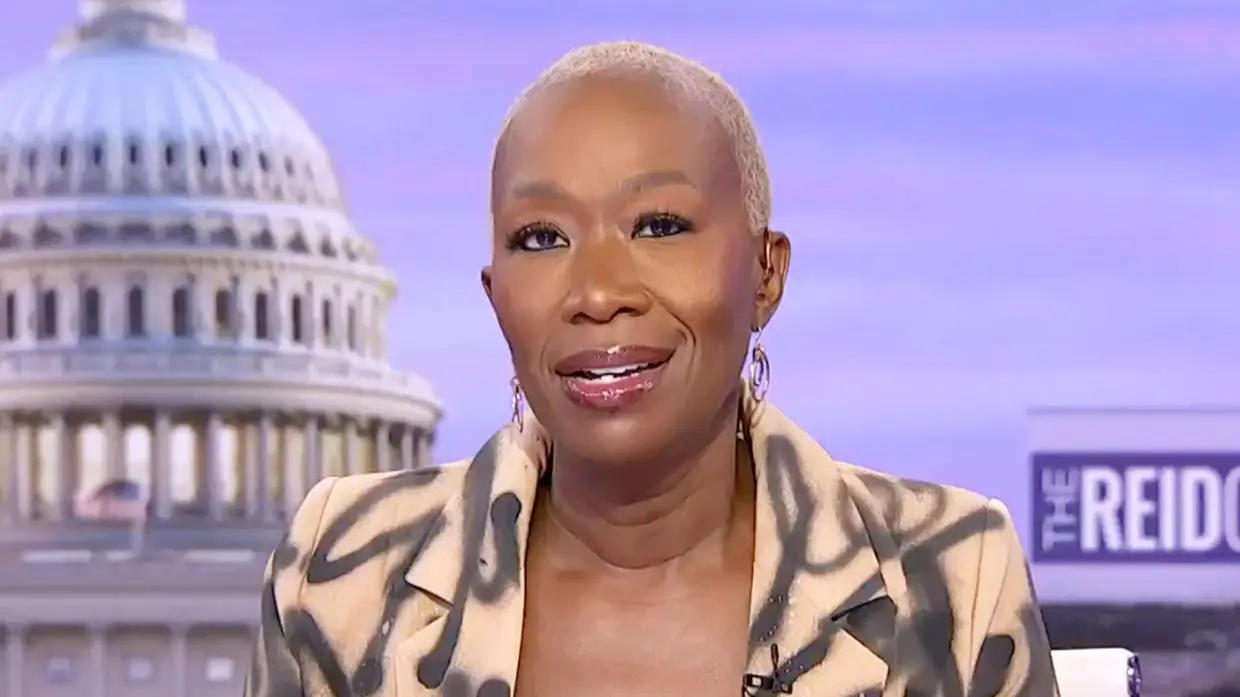

In mid-December 2025, a viral social media video resurfaced longstanding debates about the history of the beloved Christmas carol “Jingle Bells.” Former MSNBC host Joy Reid shared the clip on her Instagram account, reaching her 1.3 million followers.

The video, created by social media influencer Khalil Greene, stands beside a historical plaque in Medford, Massachusetts, and asserts that the song—originally titled “The One Horse Open Sleigh”—was composed by James Lord Pierpont in the 1850s specifically to mock Black people through blackface minstrel performances.

It further claims Pierpont was a “racist Confederate soldier” who later fought for the South and wrote pro-slavery songs.

Reid captioned her repost with comments highlighting the song’s alleged ties to minstrelsy, stating, “Jingle Bells has its origins in minstrelsy that mocked Black people.

This is the history we need to acknowledge.” The post quickly ignited backlash, with critics accusing Reid of fueling a “war on Christmas” and exaggerating historical context for outrage.

Conservative outlets like Fox News, the New York Post, and the Daily Wire amplified the story, framing it as another example of progressive overreach in labeling cultural traditions as racist. Meanwhile, some progressive voices defended the sharing of the video as an opportunity to confront uncomfortable American history.

This controversy is not new; similar claims circulated in 2017 following academic research, leading to temporary bans of the song in some schools. As of December 23, 2025, the debate continues online, with memes, fact-checks, and heated discussions dominating social media. But what does the historical evidence actually show?

The Origins of “Jingle Bells”

“Jingle Bells” was composed by James Lord Pierpont (1822–1893), an organist and music teacher with a tumultuous life marked by financial struggles and family divisions.

Pierpont, son of a staunch abolitionist minister, rejected his Northern roots, moved South, and supported the Confederacy during the Civil War, serving as a clerk and writing pro-Southern songs. His nephew was the financier J.P. Morgan.

The song, first copyrighted in 1857 as “The One Horse Open Sleigh,” describes a joyful winter sleigh ride, complete with bells on the horse’s harness (a practical safety feature in snowy conditions to alert others), racing, and an upset in the snow. It was renamed “Jingle Bells” in 1859.

Notably, it was not originally a Christmas song but a general winter tune, often associated with Thanksgiving or sleigh races in 19th-century New England.

The lyrics themselves contain no explicit racial references, slurs, or dialect typical of overtly racist minstrel songs of the era. Lines like “dashing through the snow” and “laughing all the way” evoke lighthearted fun, with themes of courtship and mishaps.

The Minstrel Show Connection

The core of the controversy stems from a 2017 peer-reviewed article by Boston University theater historian Kyna Hamill, published in Theatre Survey.

Hamill’s research, intended to resolve a dispute over whether the song was written in Medford, Massachusetts, or Savannah, Georgia, uncovered archival evidence: the song’s first known public performance occurred on September 15, 1857, at Ordway Hall in Boston, a venue popular for minstrel shows.

Minstrel shows were a dominant form of American entertainment in the mid-19th century, featuring white performers in blackface caricaturing Black people through exaggerated stereotypes, dialect, and mockery.

Hamill documented that the performer, Johnny Pell (of Ordway’s Aeolians troupe), appeared in blackface, portraying “Dandy Darkies”—a common trope of flashy, urban Black characters.

Hamill argued that the song entered popular culture through this racist performance tradition, and over time, its “blackface and racist origins have been subtly and systematically removed from its history.” She noted similarities to other sleigh-themed minstrel songs that explicitly burlesqued Black participation in winter activities, which were rare in the South but idealized in Northern imagery.

However, Hamill has repeatedly clarified that her findings have been misrepresented. In interviews with outlets like the Boston Herald and The Guardian, she stated: “I never said it was racist now” or that the song was intentionally written as mockery.

She emphasized that she was documenting performance context, not calling for the song to be banned or deeming modern sing-alongs racist. “It was obviously an easy way to bait and politicize Christmas,” she said of the backlash.

Fact-checks from sources like Snopes and Factually.co corroborate this: while the debut performance was in a minstrel setting, there is no direct evidence Pierpont composed the song explicitly to satirize Black people. The printed lyrics lack minstrel dialect, and sleigh rides were a genuine Northern pastime.

Viral Claims and Misinterpretations

The 2025 video shared by Reid goes further than Hamill’s research, alleging the song was “written to make fun of Black people” and linking “laughing all the way” to a minstrel routine called the “Laughing Darkie.” Some social media posts have invented additional myths, such as bells being placed on enslaved people’s necks for tracking (debunked; bells were for horses).

These exaggerations echo 2017-2019 cycles, when misreporting led to schools like Council Rock Primary in New York temporarily removing the song from curricula. Scholars note that while minstrelsy was inherently racist, not every song performed in that context was composed with racial intent—many neutral tunes were adapted.

Public Reaction and Broader Implications

The Reid post drew sharp divisions. Critics, including commentators on Fox News and outlets like OutKick and Townhall, called it “race-baiting” and evidence of liberals seeking to “cancel” holiday joy.

Figures like Charles Payne on Fox Business decried it as making Black people “feel like crap.” On X (formerly Twitter), users mocked the claim with parodies and defenses of the song’s innocence.

Supporters, including some Black creators and outlets like EURweb and Black Enterprise, argued that acknowledging historical context enriches understanding without ruining the song. They point out that many American traditions have complex pasts intertwined with racism, and ignoring them perpetuates erasure.

As of late December 2025, no widespread bans have resulted, and “Jingle Bells” remains a staple in holiday playlists, commercials, and performances worldwide. Streaming data shows no dip in popularity.

Conclusion: History vs. Modern Meaning

The evidence supports a nuanced view: “Jingle Bells” has documented ties to the racist institution of blackface minstrelsy through its debut performance, and its composer held pro-Confederate views. This context reflects broader patterns in 19th-century American culture, where entertainment often reinforced racial hierarchies.

However, claims that the song was deliberately written to mock Black people overstate the research. The lyrics are innocuous, focused on universal winter merriment, and the song evolved into a secular holiday classic detached from its origins.

Debates like this highlight ongoing tensions over how to reckon with America’s racial history. Sharing such information can educate, but sensationalism risks division without adding clarity.

Ultimately, whether one chooses to sing “Jingle Bells” today is a personal decision—its cheerful melody endures for most as a symbol of joy, not harm.

News

“I Felt Like a Fraud.” — Henry Cavill Confesses He Almost Quit the Movie During Rehab, Convinced He Was Too Old to Play an Immortal Warrior at 42.

“I Felt Like a Fraud.” — Henry Cavill Confesses He Almost Quit ‘Highlander’ During Rehab The man chosen to play…

“He Won’t Speak to Us.” — Henry Cavill Goes Silent on the ‘Highlander’ Set, Refusing to Break Character Even When the Cameras Stop Rolling.

The easy smile is gone. The small talk has vanished. In its place, crew members say, stands Connor MacLeod. As…

“I Begged for This.” — Dave Bautista Waited 10 Years for One Role, and First Photos Prove He Was Born to Destroy Henry Cavill’s Connor MacLeod.

For a decade, Dave Bautista has been unusually candid about one ambition: he wanted to play The Kurgan. Not casually….

Live on TV, a Reporter Tries to Brand Fans “Toxic”—Henry Cavill Cuts Him Off Cold, Redefines Fandom in 7 Words, and Sparks a Moment Millions Still Cheer.

Henry Cavill, the actor most famously known for playing Superman in the DC Extended Universe and Geralt of Rivia in…

“Have Some Self-Respect” — Henry Cavill Draws a Hard Line as Toxic Fans Target His Girlfriend, Delivering the Most Savage Clapback of His Career

Henry Cavill has long been known as one of Hollywood’s last true gentlemen—soft-spoken, polite, and deeply respectful of his audience….

“Superman is washed up at 42”: Henry Cavill’s girlfriend posts an eight-second video of his 200kg deadlift that ends the entire online career debate.

British cinema star Henry Cavill, who turned 42 this year, has recently faced a flurry of dismissive online commentary suggesting his…

End of content

No more pages to load