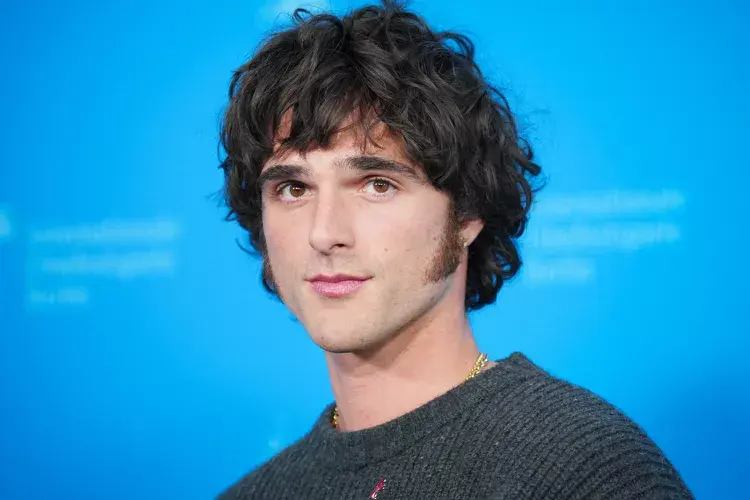

“I thought I was going to freeze to death, but this was the only way to bring my childhood dream from Lord of the Rings back to life!” Jacob Elordi shakily recalls struggling for three days and nights in -35°C freezing cold in Northern Ontario, with 54 silicone pieces glued tightly to his face.

Just as he was about to give up, Guillermo del Toro whispered something that made Elordi break down in tears, and then explode on screen, creating the “heartbreakingly beautiful monster” the whole world admires.

The first time Jacob Elordi saw a behind-the-scenes photo of himself in full creature makeup for Guillermo del Toro’s top-secret passion project Frankenstein, he didn’t recognise the face staring back. Sunken black eyes, mottled grey-green skin, jagged sutures running from temple to jaw, frost clinging to every ridge and scar.

“That’s not me,” he whispered to his manager. Del Toro, standing behind him, simply smiled and said, “Yes it is. You just haven’t met him yet.”

What the world now calls “the performance of the decade” almost never happened.

In January 2025, deep in the frozen wilderness outside Thunder Bay, Ontario, temperatures dropped to −35 °C with wind chill pushing it closer to −50 °. Del Toro had chosen the location deliberately: no green-screen, no LED walls, only real snow, real ice, real pain.

The Creature had to feel cold in his bones, because only then would the audience feel it too.

Jacob Elordi, 6′5″ and usually built like a Greek statue, lost 28 pounds for the role. Every morning at 2 a.m., a six-person prosthetics team spent five and a half hours gluing 54 individual silicone appliances to his face, neck, and hands.

The glue had to be warmed with hairdryers so it wouldn’t freeze on contact with his skin. By the time they finished, the sun was still hours from rising and Jacob’s eyelashes were already iced shut.

On the third consecutive night of shooting the Creature’s rebirth sequence, something broke.

Elordi was suspended ten feet off the ground on a tuning-fork rig in nothing between him and the blizzard except a thin layer of latex and yak hair. His core temperature had dropped dangerously low. The on-set medic was screaming numbers no one wanted to hear.

Between takes he couldn’t stop shaking, tears freezing on the prosthetics before they could fall.

He signalled to be lowered. “I’m done,” he rasped through chattering teeth. “I can’t feel my face. I can’t feel anything. I’m quitting the scene.”

Del Toro didn’t argue. He simply walked through the knee-deep snow, took off his own massive parka, wrapped it around the shivering actor, and pulled him close until their foreheads touched. Then, so quietly that only Elordi could hear over the howling wind, he whispered:

“If you can endure these three days, you will make all of Hollywood cry… and you will finally give that little boy in Brisbane, who stayed up all night reading The Lord of the Rings under the covers with a torch, the monster he always knew was beautiful.”

Elordi says the world went silent.

He thought of himself at eleven years old, obsessed with Tolkien, with Andy Serkis’ Gollum, with the idea that the most terrifying creatures were the ones who only wanted to be loved. He had spent years chasing “cool” roles, heartthrob parts, anything that kept him pretty and safe.

And here was del Toro handing him the chance to become the very thing he had worshipped as a child, at the cost of almost killing himself in the snow.

He started sobbing, huge, uncontrollable gasps that cracked the makeup department spent forty minutes repairing. Then he looked at del Toro, nodded once, and said, “Put me back up.”

What happened next has already become set lore.

For the final take, Elordi didn’t act the Creature waking up. He became it. When the lightning hit and his eyes snapped open, wide, wet, ancient, the entire crew audibly gasped. The camera operator forgot to call cut.

Del Toro just stood there weeping behind the monitor, whispering “Sí… sí… mi niño hermoso…”

When they finally yelled cut, the 120-person crew broke into applause that echoed across the frozen Lake Nipigon. Elordi was lowered, half-conscious, wrapped in heated blankets, and carried to the warmth tent. He doesn’t remember the walk.

He only remembers del Toro kissing his frostbitten forehead and saying, “You did it. You made the monster human.”

Early test screenings have reportedly left executives speechless. One studio insider told Variety: “I’ve seen the reel. Grown men were crying in the bathroom afterwards. It’s not just a performance. It’s a resurrection.”

Del Toro himself, normally effusive in interviews, has been unusually reverent when asked about Elordi’s work: “Some actors give you their craft. Jacob gave us his soul, piece by frozen piece. There is before this movie, and there is after. Nothing will look the same.”

As for Elordi, he still can’t watch the footage without shaking.

“I almost died bringing him to life,” he told Vanity Fair last week, voice soft. “But I would do it again in a heartbeat. Because for twelve minutes on screen, I got to be the most heartbreaking thing I ever imagined as a kid.

And the whole world finally saw him the way I always did: not scary. Just… lonely.”

Guillermo del Toro’s Frankenstein, starring Jacob Elordi as the Creature, Oscar Isaac as Victor, and Mia Goth as Elizabeth, is currently in post-production for a December 2026 release.

The little boy from Brisbane who once dreamed of monsters finally became one.

And Hollywood is still trying to thaw out from what he did up there in the snow.

News

“NO TEAM WILL SIGN ME!” No USA swimming team is reportedly willing to accept Lia Thomas after her ban from the Olympics and Thomas’ refusal to take a gender test.

The swimming community is abuzz with heartbreak and controversy as transgender swimmer Lia Thomas faces an uncertain future. Banned from…

SHOCKING NEWS: Fan Captures Jon Bon Jovi Crying Mid-Concert in New Jersey Social media is in an uproar after a fan video surfaced showing Jon Bon Jovi breaking down in tears during one of his most emotional performances. The footage, captured during his New Jersey show, shows the rock legend pausing mid-song as his voice cracked on the final verse of “Bed of Roses.” Witnesses say the arena fell silent as Jon lowered his head, visibly overcome with emotion.

It was supposed to be another unforgettable night of rock ’n’ roll in New Jersey — the kind of night Jon…

Brandi Carlile: America the Beautiful Singer at Super Bowl 2026

Brandi Carlile out Lesbian songwriter, producer, and activist known for music that spans folk rock, alternative country, Americana, and classic…

What makes a guitarist’s tone so recognizable that it becomes the backbone of a band’s identity?

What makes a guitarist’s tone so recognizable that it becomes the backbone of a band’s identity? Richie Sambora provided that…

Blud brothers: how Aerosmith and Yungblud made magic together and landed a No. 1 album

After Steven Tyler suffered a life-changing throat injury in 2023, it was uncertain whether Aerosmith would ever record again. That…

Avenged Sevenfold and Good Charlotte have announced a 2026 North American co-headlining tour.

The trek kicks off in Missouri in late July and wraps up in Arizona at the end of August. They’ll…

End of content

No more pages to load